I grew up wondering about the world that lay beyond the tumbleweeds and pumpjacks of my home in West Texas. Reading, road trips, and French studies offered glimpses of what was out there waiting for me. College heightened my appetite for the blue yonder, sparking a summer adventure in Mexico and an 8-month stay in France. Within a year of graduation, I joined the Peace Corps and headed to Ivory Coast, West Africa. The capital city of Abidjan was the starting point for orientation, language, and teacher training. Since I already spoke French, I got to study Dioula, a tonal language that is still the lingua franca of trade across Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ivory Coast.

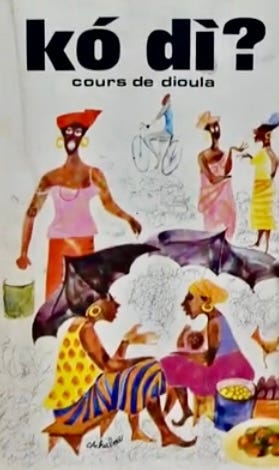

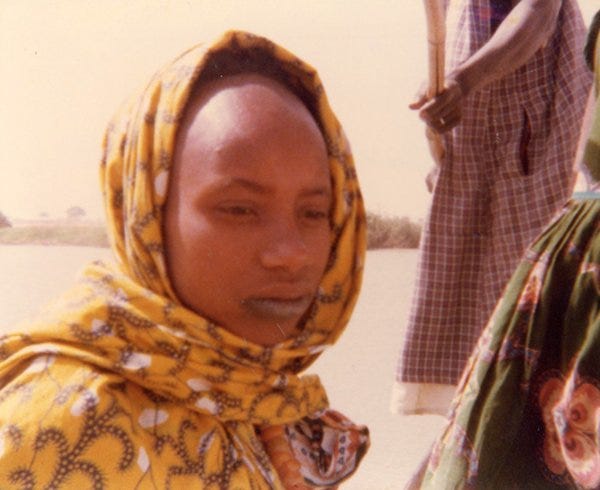

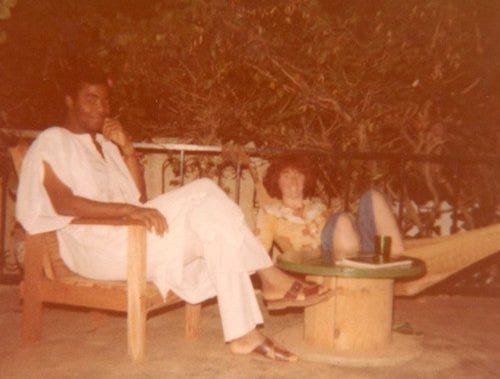

Back then, Dioula became the key to everything—helping me navigate the everyday and encouraging my forays far afield. Volunteers who came before were taught in the oral tradition. Nothing in print existed until the University of Abidjan published Ko di?* (What Do You Say?), in 1974. Today, if you visit my studio in the States, you’ll find a copy of the first edition on the bookshelf. Linguist Mamadou Ba helped write the book (cover detail pictured here). He was my first teacher. You can see him standing on the far left in the photo below.

We volunteers soon discovered the value of knowing how to speak at least a few magic words. In the open-air markets, Dioula was essential to bargain with vendors of fruit and vegetables, fabric and flip flops. Jòli? (How much?) The lingo was equally vital for communicating with purveyors of shoe and moped repair whose popup shops were close by.

Dioula would become key to travel, too. In the 1970s, larger towns had taxi gares (taxi stations, in French)—ad hoc transit hubs, where cars, covered trucks, and vans converged to take on passengers. Vehicles clustered in zones based on their intended destinations. As we walked up with our bags, a chorus of freelance transit agents would surround us, calling out, I be taa min? (Where are you going?) They’d guide us to a spot where we’d wait, often for hours, until enough travelers had arrived to fill our car or bus. Only then would we be on our way.

After student teaching in Abengourou, I arranged for a ride to the city where I would live. Nse taa Man. The 10-hour drive west along winding red clay roads ended as darkness rose in the foothills of Mont Tonkoui. In Man, I lost no time in seeking out the local junior high school teacher known to be a stellar Dioula instructor. His name was Elam, a moniker rooted in the Arabic word al 'alam, meaning highland.

At least three afternoons a week, Elam would stop by my place for lessons. There were days when we’d sit on the terrace so I could practice reading and writing. But mostly we’d wander the hilly streets. The city and its people became my classroom—readymade stage and characters for the stories I learned to tell. Elam led me into a cultural space that I could have never imagined knowing. No wonder my guide became a dear friend.

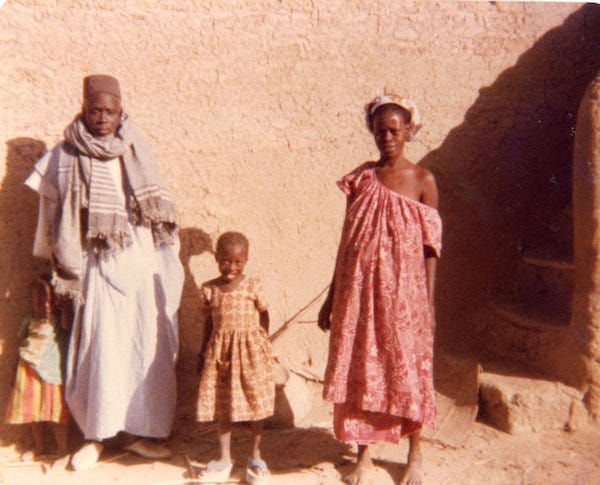

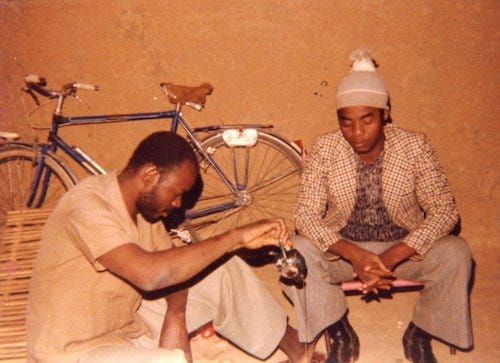

During winter holidays in 1977, we took an epic field trip, traveling together from Ivory Coast to Mali. We rode in a lorry, stopping at the border in the early morning to wait for the customs house to open. The next day, we arrived in Ségou to visit Elam’s brother Solomon. We stayed in the compound where Solomon lived with his beautiful wives and children. In Dioula, I embraced their warm welcome. Foli! (Thank you!) Evenings in the courtyard, Solomon brewed mint tea over a small burner. The ritual made time stand still, conjured hours of quiet conversation beneath the starlit sky.

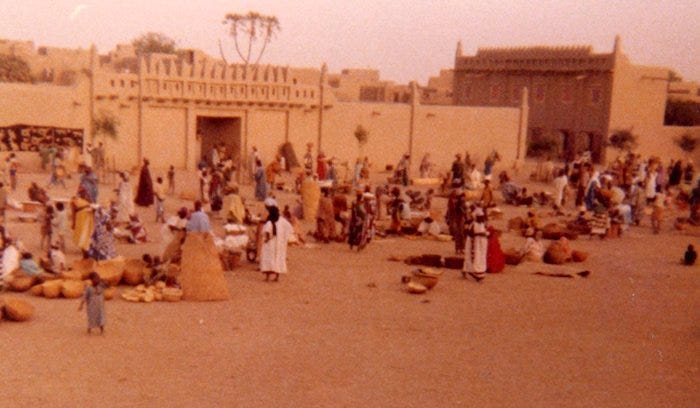

A few days later, I left on my own to explore further north, traveling by truck to Mopti and then taking a ferry to Djenné. Everywhere I went, Dioula was my passe-partout, the key to a journey that still shimmers in my mind.

Read my first story from Ivory Coast HERE.

*If you’re fluent in Dioula or Bambara, please share suggestions for the phrases I’m using. I haven’t spoken the language since 1978.

Sampled music: Djelimoussa Sissoko - Mali Kora

Learn more about the authentic Texas tumbleweed that drives this narrative HERE.

The world would be so different if all young people experienced different worlds and different words for what they have always known. What a journey!

I love learning about your lifelong travels!